MediaScout

MediaScout is a webapp that takes information of movies, tv series and actors from an API and shows it to the user. Users can also search for media and see similar movies and shows by genre/keywords.

Motivation

I planned to make this project to learn how to work with APIs better with varying types of requests and parameters. I chose to user the TMDB API to query and display results as it was well-known, easy to use, and did not have any rate limits and was completely free.

Like the previous project, I used vanilla HTML, CSS(with Bootstrap) and JS for the frontend and a Flask API for the backend.

The structure

The project mainly had 4 sections:

- Home

- Movies

- TV

- Search Results

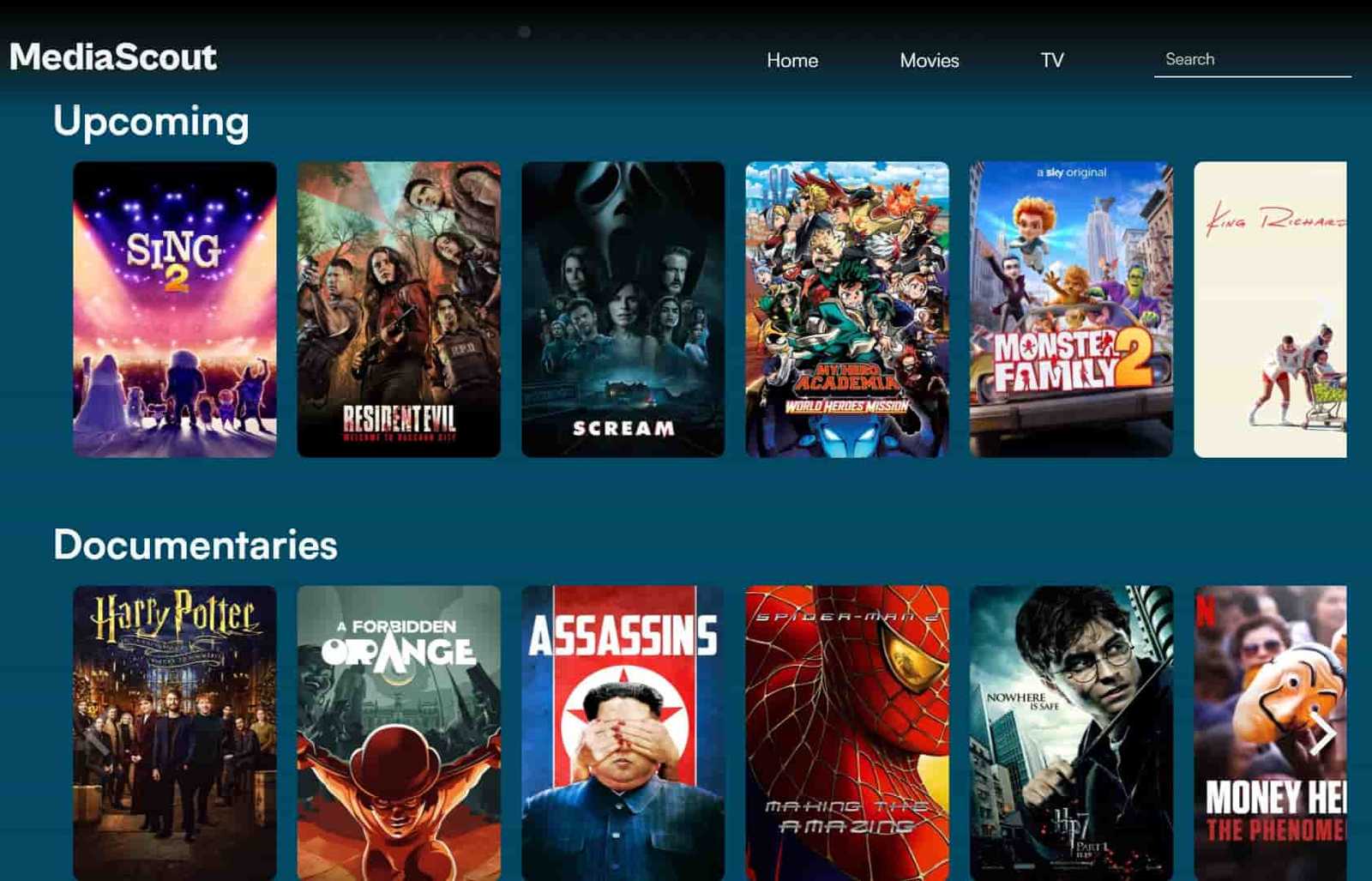

The Home, Movies and TV sections would make requests to the API for media of a particular category like Trending, New Releases, Top Rated or by genre like Documentaries, Crime, Animation.

This is how the main movie page looks like:

An example of a request made to the API:

def info_by_category(self, category_after, media_type, category_before=None):

"""Returns the information on media of a particular category like 'trending' or 'popular'."""

return self.get_general_info(

f"https://api.themoviedb.org/3{ ('/' + category_before) if category_before else ''}/{media_type}/{category_after}",

media_type=media_type,

)Storing homepage data in databases

The above code snippet is to get the information of ONE category of media. For a homepage, this means the site will have to make multiple concurrent requests to the API. I can load the data asynchronously, but the pages would still be heavily slowed down and this would lead to a bad experience for any user.

I then decided that the best alternative would be to store the homepage data in a database. This would speed up the loading time as no requests would be made to the API.

Updating the data, however, was a problem I had not handled before.

After some digging, I set up pymongo and a database on MongoDB Atlas. It’s free and more than enough for small projects.

The process was simple:

tv_home = db.media_data.update_one(

{"page": "tv_home"},

{"$set": {"content": get_tv_home_info()}},

upsert=True,

)I then created a /update-db/<id> route on the application to handle a route and take a parameter id. This would

later get changed to a simple POST request with the id in the passed JSON.

The id is a UUID

and would be compared to the id stored as a environment variable every time the path /update-db

was visited. If the id did not match, the user would get a

403 response. As a result, only those

with the correct ID would be able to update the database. This was to prevent overloading the TMDB API with requests.

Updating the DB periodically meant using a cron job that would ping the /update-db

route at a specefic time every day. While we can set up our cron jobs on our own servers, for such small operations,

GitHub Actions was my first option. The advantage it had was being really easy to

set up in the repo as it was a feature in GitHub itself.

To set it up, I created a file called update_database.yml in a folder workflows in the .github folder. This would tell

GitHub that the .yml file is meant to be used for an Action.

The contents of the file are as follows:

update_database.yml

# The name of the action

name: Refresh database with updated media data

on:

schedule:

# Run at 6 AM every day

- cron: "0 6 * * *"

jobs:

update-database:

runs-on: ubuntu-latest

steps:

- name: trigger-update

run: |

curl --location --request POST 'https://mediascout.onrender.com/update-db' \

--header 'Content-Type: application/json' \

--data-raw '{"auth_code": "${{secrets.UPDATE_TOKEN}}"}'As you can see above, the job is set to run on a schedule and has only one step. If you want to learn more, visit crontab.guru to get a better undertanding of the syntax.

So, at that particular time, the server hosting the action would send a POST request to the /update-db route with the

id. The app would then check the ID and start updating the database.

As a result, the homepage issues were sorted out!

Viewing media details

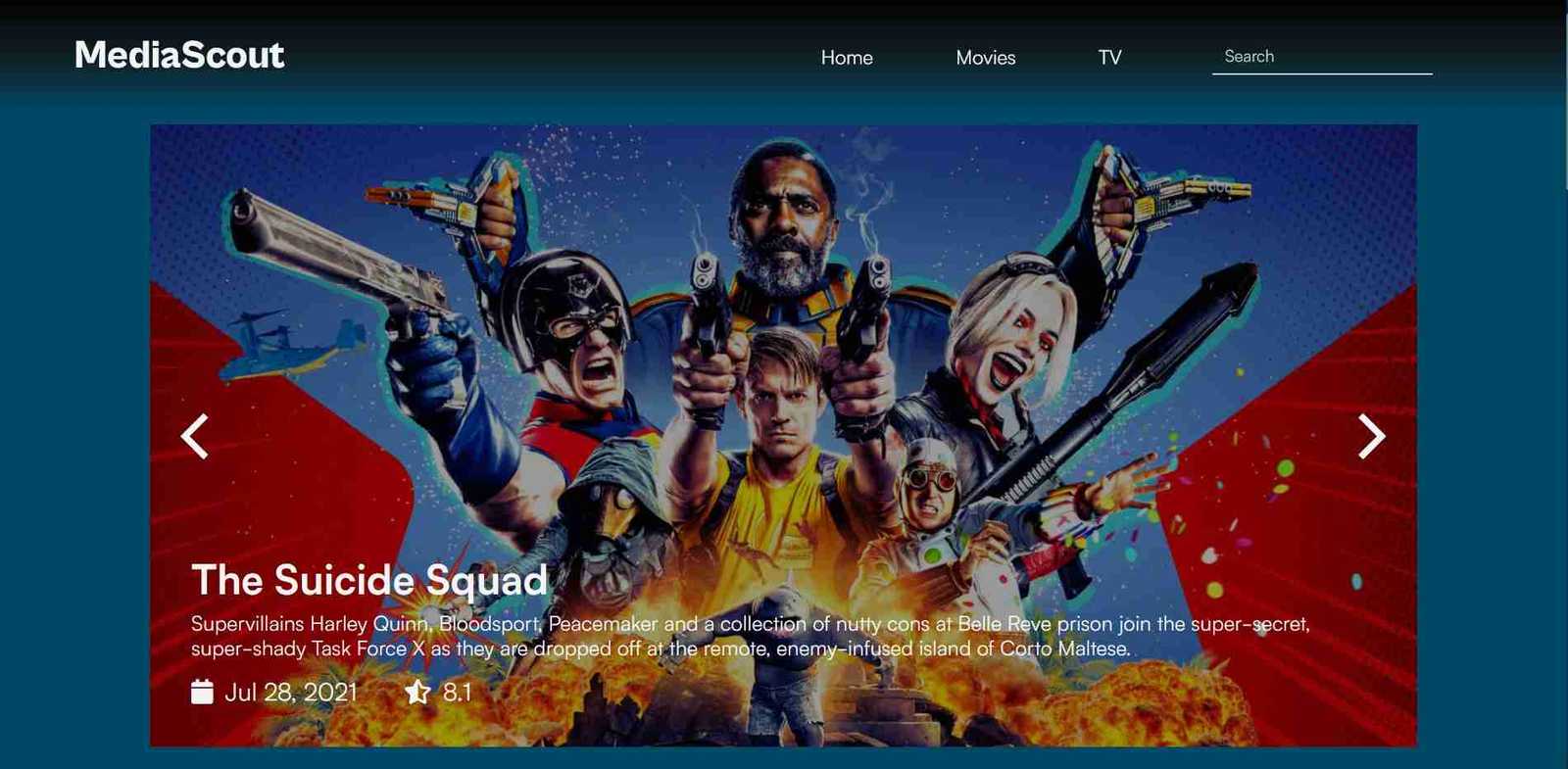

Once a thumbnail is clicked, another request is made to the API, asking for the details of the media.

I initially used to just pass all of the results to the template without formatting and placed all logic into the templates. This paragraph, however, changed my mind and I transferred most of the logic to the backend while just displaying them in the template.

The simplify_response()

function contains most of the logic transferred from the templates. It mostly converts linkable data to links (like actor details) and

simplifies the rest of the results to show just the main information like Directors, Languages, Companies, etc.

This is how a media detail page looks like:

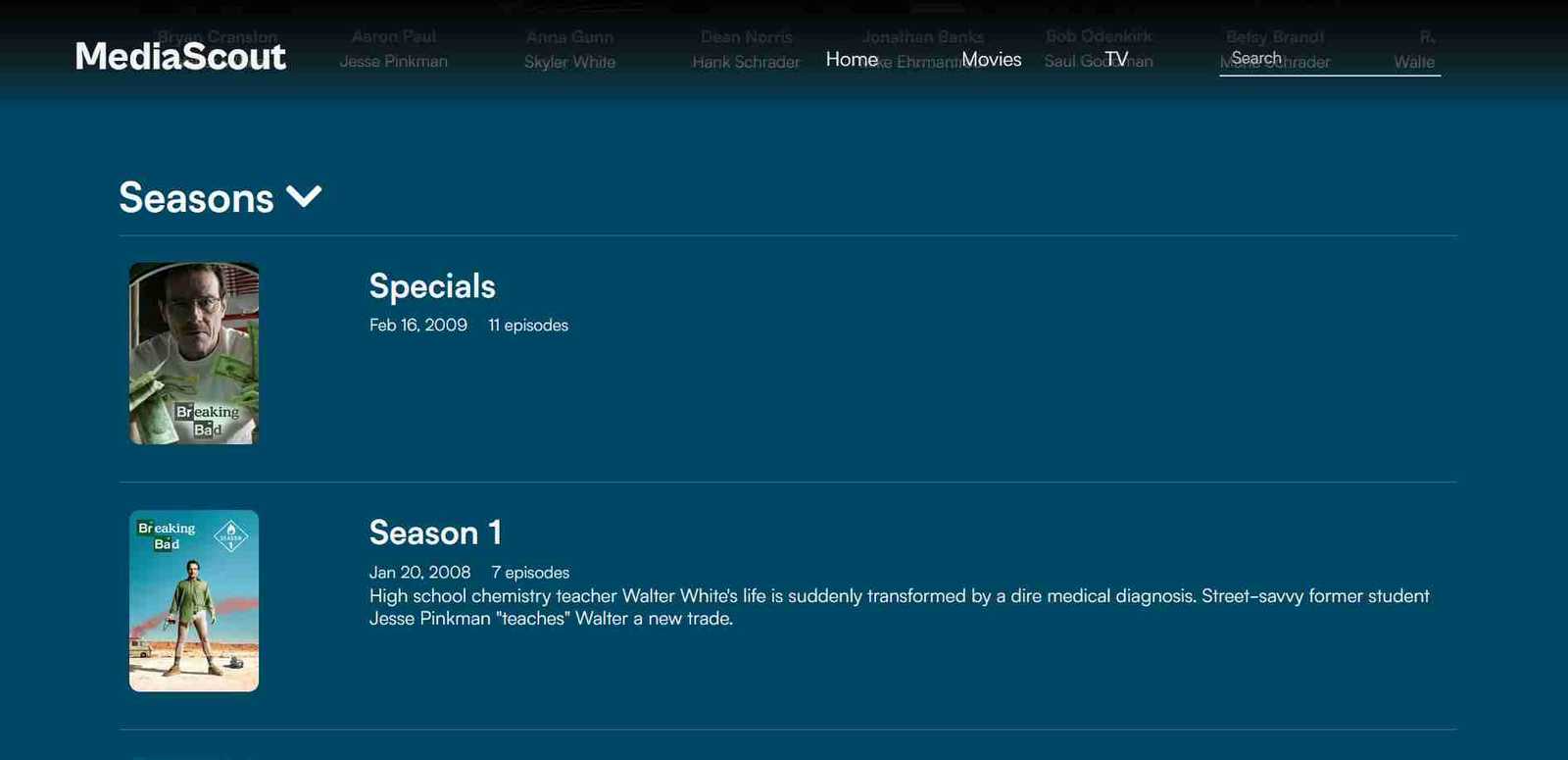

TV details

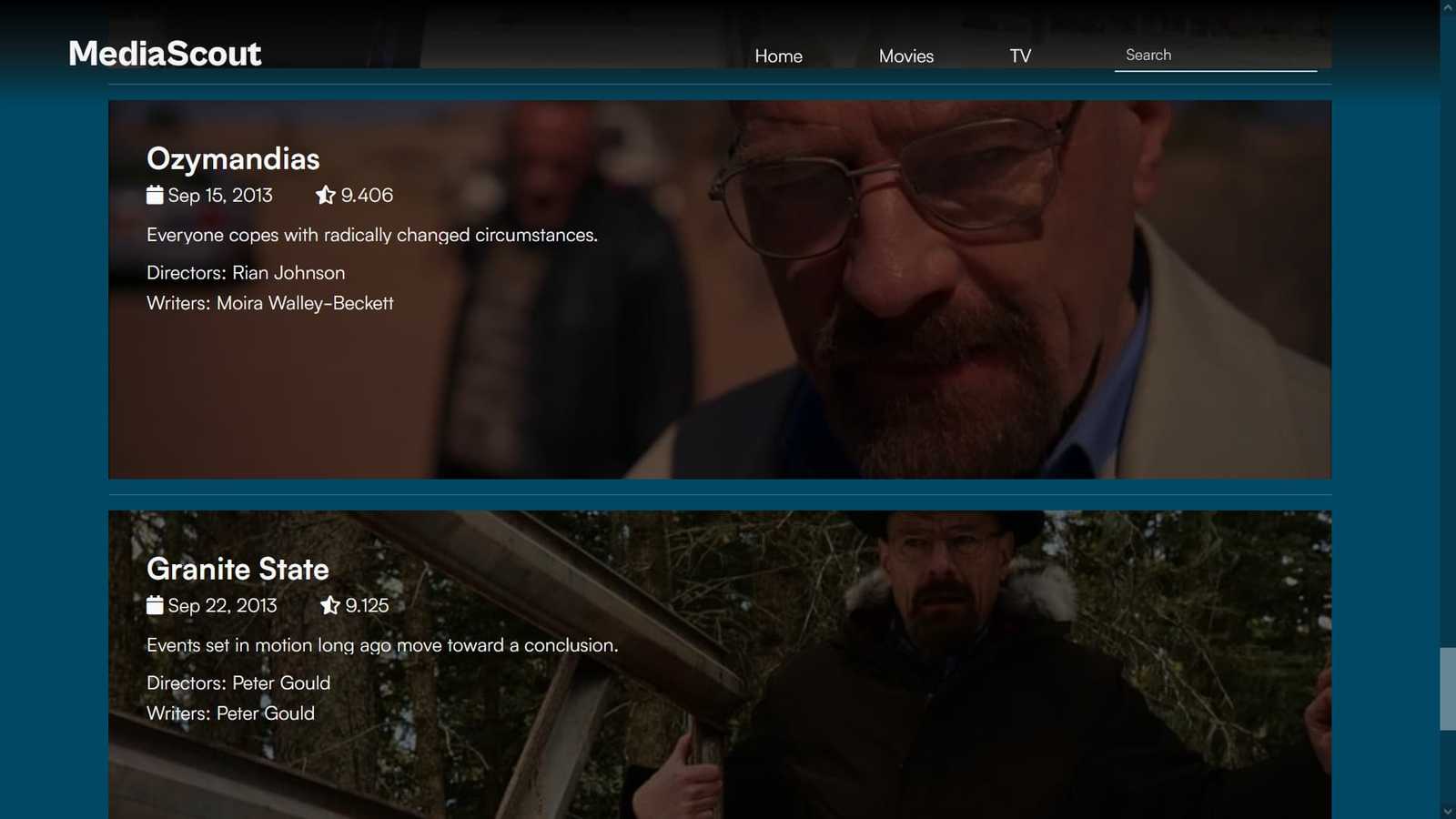

If the media being viewed is of a series, the seasons and their descriptions are also shown to the user.

The seasons too, can be clicked to show small descriptions of each episode.

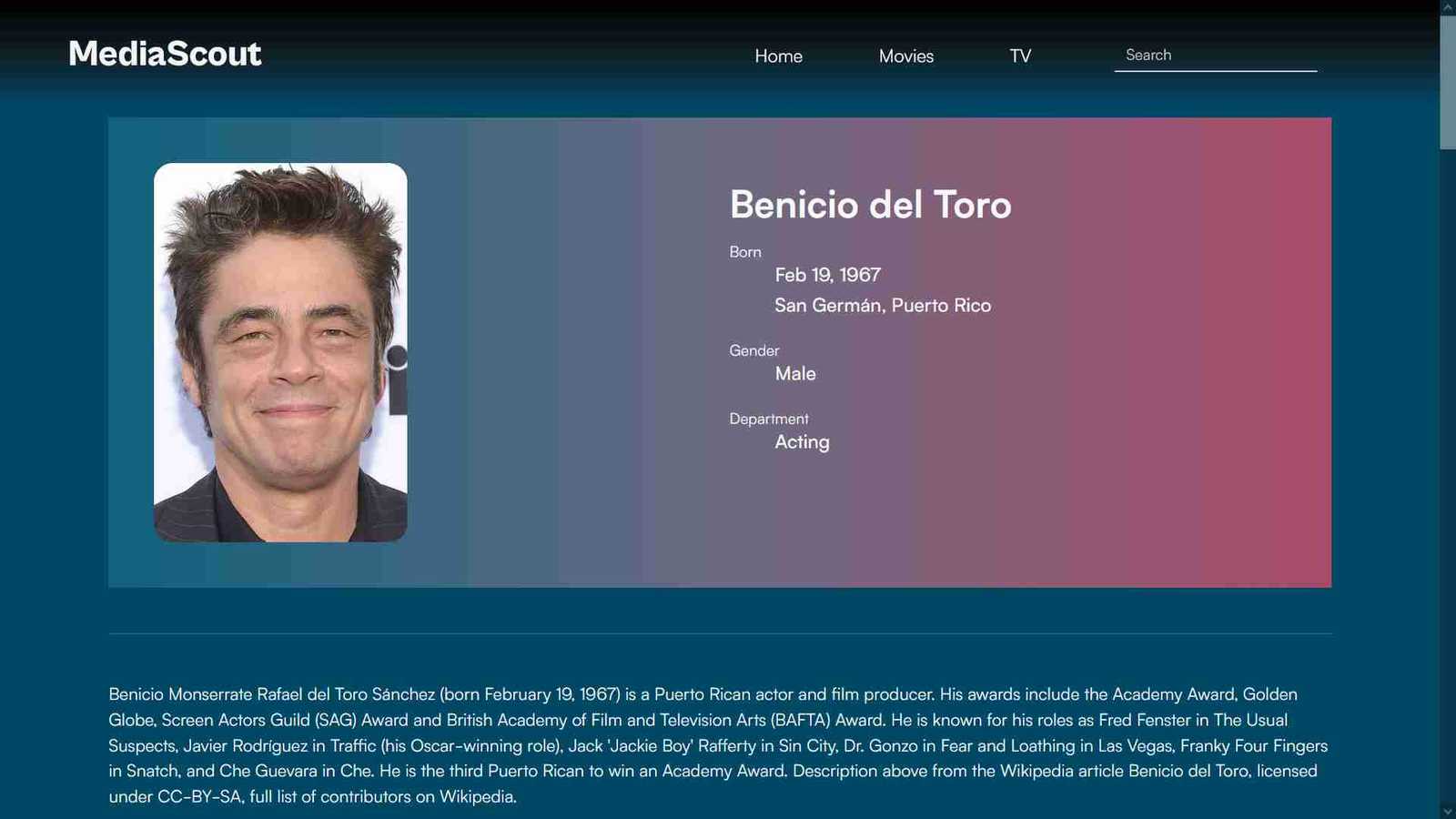

Actor information

Information of actors (description and filmography) can also be searched and viewed. The information is requested in a similar fashion to the movie/tv details.

Searching by query and by keywords

After the description of every Movie/Series, tags given by the TMDB API are shown and can be clicked to view similarly tagged media.

On the navbar is a searchbar, through which users can search for media by a query.

The pagination for the results was also relatively easy to implement, as I had to just pass in a page number to the API to get another set of results.

Finishing up

In the end, this project(although less challenging than table2markdown) taught me a lot about interacting with APIs, using databases and speeding up pages as much as possible.

You can view the project here!

Thanks for reading!